Our Goal Should be to Delight People

When you talk to Governor’s School librarians Christina Fuller-Gregory and Michael Giller about libraries, one term that keeps coming up is “a third place.”

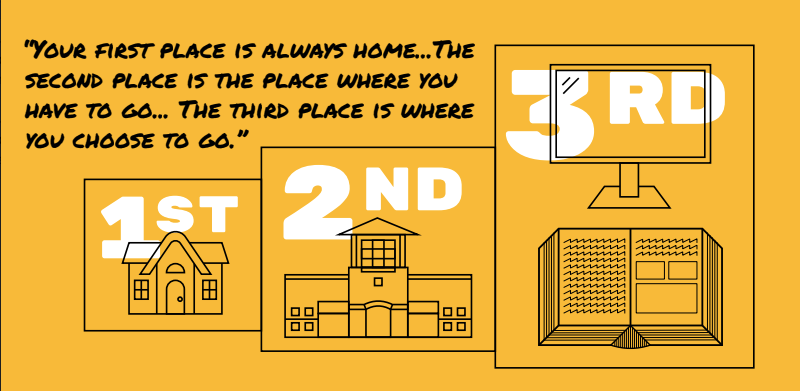

But what is a third place?

Fuller-Gregory, who recently joined the Governor’s School staff after years as a public librarian in Spartanburg County, explains it this way. “Your first place is always home, or that place where you perch, where you rest. The second place is the place where you have to go.” For some of us, this is work, for others, it might be school.

“The third place,” she says, “is where you choose to go. There’s power in the choosing—that choice.” The process of creating that “third place” is often referred to as creative placemaking, and it just happens to be one of Fuller-Gregory’s specialties.

In a recent article in Public Libraries magazine, Fuller-Gregory recalls running across Ray Oldenburg’s book, The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons and Other Hangouts in the Heart of a Community. What struck her was how precisely libraries met Oldenburg’s criteria for a “great good place.” According to Fuller-Gregory, libraries fit the bill “like the list had been made specifically for us—neutral ground, regulars, accessibility and accommodation, and easygoing environment where conversation is key, and most significantly, a home away from home.”

For Giller, libraries have served as a third-place ever since he was a high school student. He and his friends would meet there to study and pick up books on whatever they were into. “This was pre-internet days, so the library had everything you needed. Even in the subculture of hippies and punk rockers I was hanging out with, it was always cool to be intellectual.”

But interestingly, Fuller-Gregory’s experience was very different. “I hated libraries growing up. My mom is a librarian. All of her sisters are librarians. I was forced to go to every library program. I spent a long time avoiding libraries.”

She graduated college with a journalism degree and then went on to a career in marketing. But ultimately, she found herself unhappy with this line of work. She describes feeling a lack of authenticity. “I wanted real connections,” she says, and it was this desire to connect with people in a meaningful way that eventually led her back to librarianship.

In the years since her childhood days, libraries had changed, and they’ve kept changing in an effort to reach populations who, like Fuller-Gregory herself, may have resisted libraries for one reason or another. For instance, back when she was growing up, libraries primarily focused on two age groups: little kids and adults. Now, most libraries offer space and programming specifically designed for teens and young people. “When a young person discovers that there is something for them” at the library, they come away thinking, “they hear me, they see me, they want to program for me, they want to purchase materials for me. Then you’re going to have those regulars that use the library. And that’s the best feeling in the world.”

The development of those “regular” relationships is one facet of a “third place;” another important aspect centers around ideas of accommodation and conversation. Fuller-Gregory says, “I think for so long, we’ve kept away those people who are afraid to come to the library because maybe they don’t read well, or maybe they’re members of a marginalized population.” But as libraries shift from a focus on collections to concentrate more on programs, those avenues to new users are opening up.

“We’re hubs of information,” Fuller-Gregory says, “but now that information is being served in different ways. Maybe it’s not being served inside a book. Maybe it’s being served in real-time experiences.”

As an example, Fuller-Gregory points to a program she offered in Spartanburg libraries called “How Tuesdays.” The focus of these programs were not books, but skills. “They’d come in on the first Tuesday of the month, and I’d teach them how to do anything. Refurnish furniture. Repair their bicycles. Flower-arranging. We got this following because people want to learn stuff.” She also helped orchestrate a program called Make-Aways, which revolved around portable activity kits containing items like telescopes, spirographs, baking pans, or birdwatching binoculars. “I was always telling people, take away a Make-Away.”

For his part, Giller underscores the library’s role as an information source when he emphasizes the topic of media literacy. Part of his mission as a librarian is to help students use, analyze, and consume information, whether that information comes in the form of video streaming services, websites, news organizations, or public forums. In the current political climate in which disinformation is so prevalent, Giller shows students how to “verify that a piece of information is accurate. What makes it accurate? What does authenticity mean? What does it mean to be an authority on the subject? It’s not a lack of information; it’s deciding what’s real and what isn’t.”

Since Covid-19 restrictions have forced so many libraries to rely on virtual resources, Giller and Fuller-Gregory see creative placemaking moving into cyberspace, as well. As Fuller-Gregory explains, this is an opportunity for libraries to showcase the many resources they have beyond their physical collections. She points to public libraries’ collections of audiobooks and digital magazines. “I hear my friends talk about how much they love their Audible subscription. Why are you paying for Audible when you can get Overdrive at the public library for free? When you can read Time magazine, Newsweek magazine, gossip magazines, for free?”

Virtual services also make it possible to partner with other teachers and librarians from anywhere. A school librarian “might be a content creator here, but is there another school that has content creators in different areas? Now is the time for them to jump on a Zoom call and create something together.” Fuller-Gregory also suggests virtual artist residencies, which allow members of the community to interact with students, share their expertise, teach classes or run demonstrations, all from a remote location.

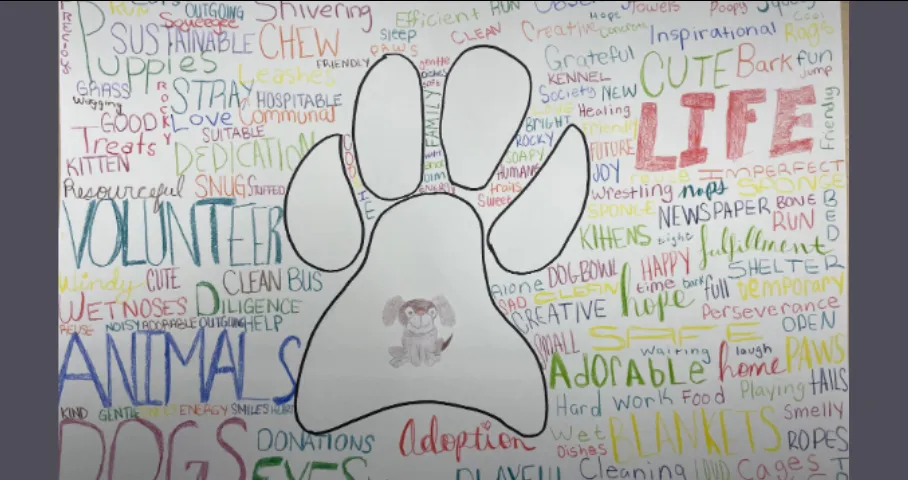

Other collaborations might take place closer to home. For example, each year Giller partners with the senior Graphic Design class for a Banned Book Week project. Giller approaches the class as if he were a client. “I say I have a need. I am a library, and I have an event called Banned Books Week.” The students then learn the background surrounding Banned Books Week, the broader history of book censorship, and the application of First Amendment Rights. Using that information, students design posters that will then be displayed in the library. It gives those students a meaningful design project, but it also gives them “a sense of ownership of the space because their artwork is going to be decorating the space.” Giller goes on to say that this kind of cross-curricular support is equally successful in a Social Studies or Civics class.

As the school year unfolds and students start to look to the library for answers and information, Giller and Fuller-Gregory hope that the students will find something more. Not just a book or a journal article, but a community, a refuge, and perhaps a kind of home. When the regulars come into the library, Fuller-Gregory says, “it is a joy for them to see each other, and a joy for me to see their faces every day.” Ultimately, she says, “our goal should be to delight people.”