Service, Sacrifice & Honor: A Daughter's Perspective

I, myself, am not a veteran. But I am the proud daughter of a veteran of two wars.

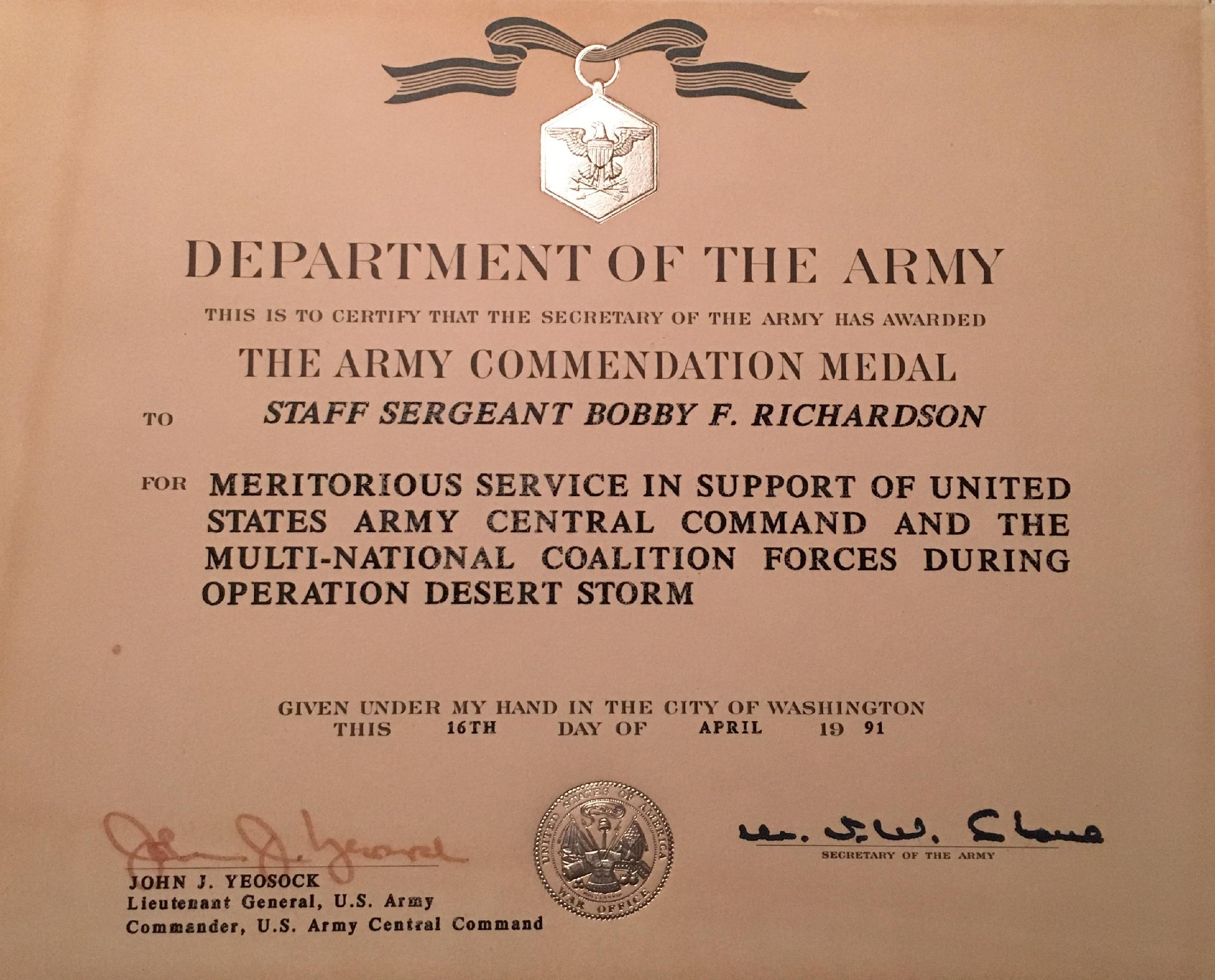

My father, Bobby Richardson, served our country in the Army’s infantry division during the Vietnam War, and he was part of the National Guard’s 228th Signal Brigade during the first Gulf War.

As a child, if I had a nightmare or woke up sick, I knew not to wake up my father. Now, I was a hardcore daddy’s girl growing up, so he was definitely my first choice. But I only woke him up once.

The next day, he sat me on his lap and explained that it wasn’t safe to shake him while he was asleep. That he sometimes had nightmares about his time as a soldier, and that he didn’t want to scare me or accidentally hurt me. Even as a child, I understood the seriousness of what my dad was saying, that he was worried for me. I wasn’t scared by his words. I simply did the thing that kids do so well. I adjusted and woke my mom up instead.

Throughout elementary and middle school, my dad was essentially "Mr. Mom." He owned his own business and was able to be a chaperone on all our school field trips. One of those trips was the 6th grade trip to Washington, D.C. There are many things I remember about that trip, but the thing I remember most was that it was the first time I saw my dad cry.

The Vietnam Memorial was a long, dark mark against the gray sky the day we visited. It was uncomfortably quiet, the clouds were heavy, and the cold drizzle matched the sadness that rolled off the adults around me.

I remember hugging my father and asking if he was okay. He tried to compose himself the best he could, and in a strangled voice, he explained that he knew too many names. Of everyone in his platoon, only seven came home. Only seven out of the 36 soldiers that he knew survived their time in Vietnam.

My father continued to chaperone the DC trip long after my sister and I moved on to junior high and high school. But he never went to the memorial again. He said it was just too painful, that it brought too many memories to the surface.

When I was in 8th grade, my dad and the rest of the 228th Signal Brigade prepared to be called up for the Gulf War. This was the 90's. Before the internet. Before cell phones. We were only able to communicate with him through the care packages we sent that took 3-4 weeks to arrive and the rare three-minute phone calls he was able to make.

There were a lot of things that my dad had to worry about. Staying alive was at the forefront. Making sure my mom, sister and I were taken care of while he was away was another. But one of the main things he wondered and worried about was how the public would react when they came back home.

You see, the Vietnam era was unkind to soldiers heading to and returning from war. My father and other soldiers were spit upon and cursed on their way to a war they did not sign up for. And upon their return, they were told to dress in civilian clothing because it wasn’t safe to walk through the airports in their fatigues. Many soldiers had rotten food thrown at them. They went from hiding in the jungle in a war zone to trying to hide in plain sight when they came back home.

So in the 90’s when the Gulf War, and the rhetoric surrounding the war, heated up, my father and many other Vietnam Vets waited on pins and needles to see how they would be treated this time.

Luckily, our country learned from its past mistakes and seemed to finally understand the difference between unpopular decisions made by our government and the soldiers who were simply following orders. My father often had tears of joy at the receptions held in honor of the veterans returning from war. He absolutely loved speaking for school assemblies. Vietnam may have taken a piece of his soul, but the love, appreciation, and admiration he and the other soldiers were shown after the Gulf War gave a bit of it back.

We often think of the loss of life when we think of war, and it truly is the ultimate sacrifice. But there are other losses to consider as well, such as missing limbs or traumatic brain injuries. There are over 19 million veterans in our country, and almost 13% have Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

My dad’s time in the Gulf War with missiles exploding overheard triggered major flashbacks of Vietnam, and he spent many years under the care of doctors as they tried to find the right medications and therapies to help manage his PTSD. This was at a time before PTSD was really understood or accepted the way it is now. In many ways, the father I loved never came home from the Gulf War. After decades of therapy and medications and life changes, I see glimpses of the father I looked up to. But I will never get back who he was. He was changed by two wars. As was my family.

My dad had to give up his work as a graphic designer because the PTSD made his hands shake too much to draw. And it took three-and-half years of doctor's visits and paperwork and documentation for the Veterans Administration to approve his disability. He now hates the 4th of July because of all the fireworks. And he is certainly not the only veteran who wishes we would celebrate the birth of our nation in a less explosive way.

But even with all that he has been through, all that he still goes.jpg) through, my dad is proud to have served his country. He has a veteran's license plate and a bumper sticker that proclaims him a veteran of the Vietnam War, and he displays his medals proudly on the wall of his home. He still does not talk about Vietnam.

through, my dad is proud to have served his country. He has a veteran's license plate and a bumper sticker that proclaims him a veteran of the Vietnam War, and he displays his medals proudly on the wall of his home. He still does not talk about Vietnam.

There is one thing my dad would ask of you today and every day—if you see a veteran, thank them for their service. You cannot know what those simple words mean to those who would lay down their lives for the freedoms we often take for granted.

Thank You, Veterans!